Happy Deathday

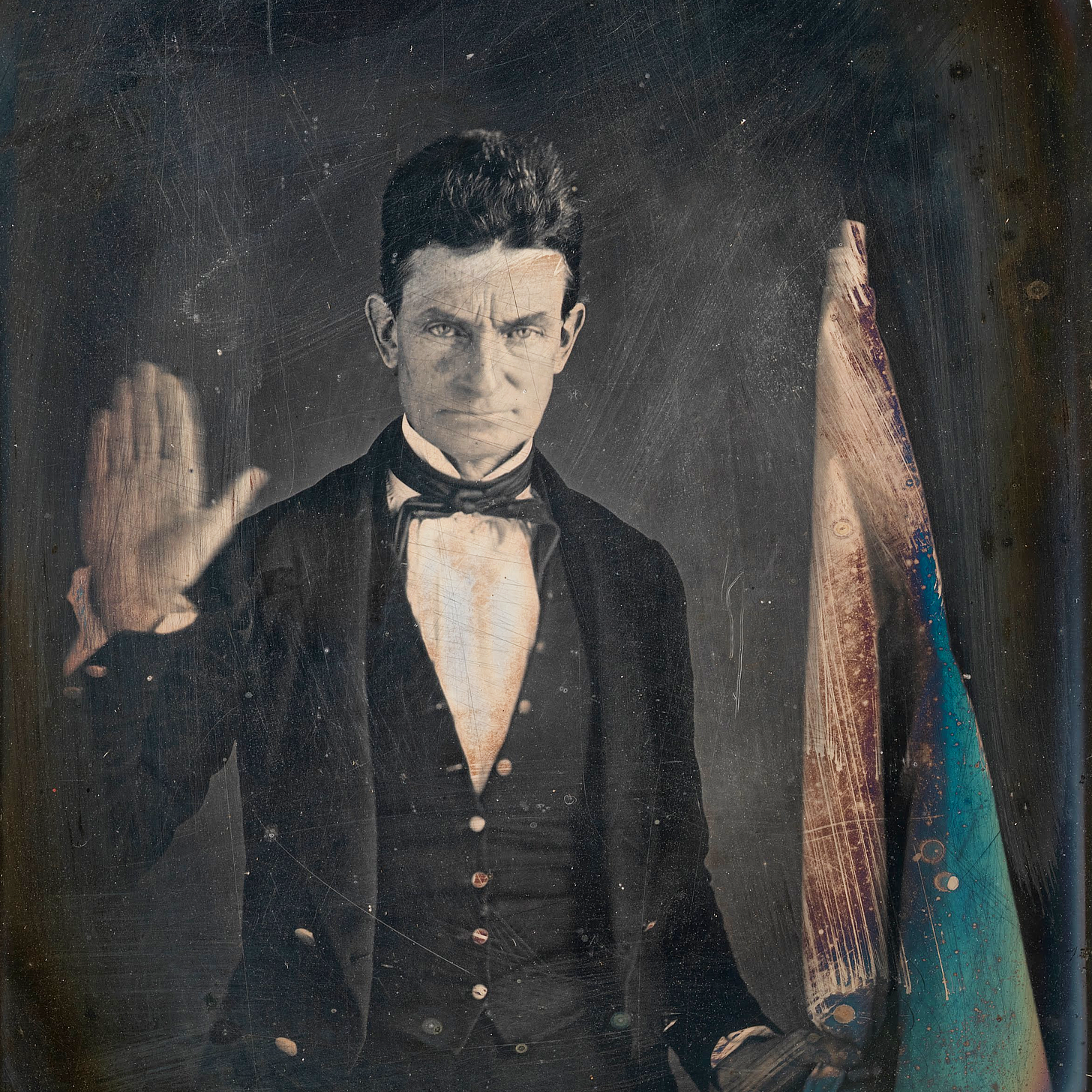

Get down with John Brown

On this day in 1859 the abolitionist John Brown was executed by the state of Virginia for his October attempt to start a slave rebellion. The attempt involved 22 men including Brown himself and three of his sons. Ten of the 22 died in action, five escaped, and seven including Brown were captured, put on trial, convicted, and executed. It was the conduct of those seven between arrest and execution that helped to make them into heroes for abolitionists, for the northern side of America’s civil war, and for many lefties today.

Brown was a deeply religious man, and in some senses a deeply patriotic man. As Wikipedia puts it:

An evangelical Christian of strong religious convictions, Brown was profoundly influenced by the Puritan faith of his upbringing. […] Brown was the leading exponent of violence in the American abolitionist movement, believing it was necessary to end American slavery after decades of peaceful efforts had failed. Brown said that in working to free the enslaved, he was following Christian ethics, including the Golden Rule, and the Declaration of Independence, which states that “all men are created equal”. He stated that in his view, these two principles “meant the same thing”.

Brown said this at his trial:

The court acknowledges, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed here which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament. That teaches me that all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so to them. It teaches me further to “remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them.” I endeavored to act up to that instruction. I say, I am too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe that to have interfered as I have done—as I have always freely admitted I have done—in behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong, but right. Now if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments—I submit; so let it be done!

Henry David Thoreau was captivated by Brown. In his home of Concord, Massachusetts, Thoreau gave a speech about Brown while Brown was on trial in Virginia. It was later published as “A Plea for Captain John Brown” and includes these gems:

When I expressed surprise that he could live in Kansas at all, with a price set upon his head, and so large a number, including the authorities, exasperated against him, he accounted for it by saying, “It is perfectly well understood that I will not be taken.” Though it might be known that he was lurking in a particular swamp, his foes commonly did not care to go in after him. He could even come out into a town where there were more Border Ruffians than Free State men, and transact some business, without delaying long, and yet not be molested; for, said he, “No little handful of men were willing to undertake it, and a large body could not be got together in season.”

Brown did not attribute his success, foolishly, to “his star,” or to any magic. He said, truly, that the reason why such greatly superior numbers quailed before him was, as one of his prisoners confessed, because they lacked a cause—a kind of armor which he and his party never lacked. When the time came, few men were found willing to lay down their lives in defence of what they knew to be wrong; they did not like that this should be their last act in this world.

We aspire to be something more than stupid and timid chattels, pretending to read history and our Bibles, but desecrating every house and every day we breathe in.

“But he won’t gain anything by it.” Well, no, I don’t suppose he could get four-and-sixpence a day for being hung. But then he stands a chance to save a considerable part of his soul—and such a soul!—when you do not. No doubt you can get more in your market for a quart of milk than for a quart of blood, but that is not the market that heroes carry their blood to.

When you plant, or bury, a hero in his field, a crop of heroes is sure to spring up. This is a seed of such force and vitality, that it does not ask our leave to germinate.

Many, no doubt, are well disposed, but sluggish by constitution and by habit, and they cannot conceive of a man who is actuated by higher motives than they are. Accordingly they pronounce this man insane, for they know that they could never act as he does, as long as they are themselves.

Ye needn’t take so much pains to wash your skirts of him. No intelligent man will ever be convinced that he was any creature of yours. He went and came, as he himself informs us, “under the auspices of John Brown and nobody else.”

These alone were ready to step between the oppressor and the oppressed. Surely they were the very best men you could select to be hung. That was the greatest compliment which this country could pay them. They were ripe for her gallows.

When I think of him, and his six sons, and his son-in-law, not to enumerate the others, enlisted for this fight, proceeding coolly, reverently, humanely to work for months if not years, sleeping and waking upon it, summering and wintering the thought, without expecting any reward but a good conscience, while almost all America stood ranked on the other side—I say again that it affects me as a sublime spectacle.

I do not wish to kill nor to be killed, but I can foresee circumstances in which both these things would be by me unavoidable. We preserve the so-called peace of our community by deeds of petty violence every day. Look at the policeman’s billy and handcuffs! Look at the jail! Look at the gallows! Look at the chaplain of the regiment! We are hoping only to live safely on the outskirts of this provisional army. So we defend ourselves and our hen-roosts, and maintain slavery. I know that the mass of my countrymen think that the only righteous use that can be made of Sharp’s rifles and revolvers is to fight duels with them, when we are insulted by other nations, or to hunt Indians, or shoot fugitive slaves with them, or the like. I think that for once the Sharp’s rifles and the revolvers were employed for a righteous cause. The tools were in the hands of one who could use them.

This event advertises me that there is such a fact as death—the possibility of a man’s dying. It seems as if no man had ever died in America before; for in order to die you must first have lived. I don’t believe in the hearses, and palls, and funerals that they have had. There was no death in the case, because there had been no life; they merely rotted or sloughed off, pretty much as they had rotted or sloughed along. No temple’s veil was rent, only a hole dug somewhere. Let the dead bury their dead.

These men, in teaching us how to die, have at the same time taught us how to live. How many a man who was lately contemplating suicide has now something to live for!

They talk as if a man’s death were a failure, and his continued life, be it of whatever character, were a success.

You who pretend to care for Christ crucified, consider what you are about to do to him who offered himself to be the savior of four millions of men.

I do not believe in lawyers, in that mode of attacking or defending a man, because you descend to meet the judge on his own ground, and, in cases of the highest importance, it is of no consequence whether a man breaks a human law or not.

Some eighteen hundred years ago Christ was crucified; this morning, perchance, Captain Brown was hung. These are the two ends of a chain which is not without its links. He is not Old Brown any longer; he is an angel of light.

“Misguided”! “Garrulous”! “Insane”! “Vindictive”! So ye write in your easy-chairs, and thus he wounded responds from the floor of the Armory, clear as a cloudless sky, true as the voice of nature is: “No man sent me here; it was my own prompting and that of my Maker. I acknowledge no master in human form.” And in what a sweet and noble strain he proceeds, addressing his captors, who stand over him: “I think, my friends, you are guilty of a great wrong against God and humanity, and it would be perfectly right for any one to interfere with you so far as to free those you willfully and wickedly hold in bondage.” And, referring to his movement: “It is, in my opinion, the greatest service a man can render to God. I pity the poor in bondage that have none to help them; that is why I am here; not to gratify any personal animosity, revenge, or vindictive spirit. It is my sympathy with the oppressed and the wronged, that are as good as you, and as precious in the sight of God.” You don’t know your testament when you see it.

When I now look over my commonplace book of poetry, I find that the best of it is oftenest applicable, in part or wholly, to the case of Captain Brown. Only what is true, and strong, and solemnly earnest, will recommend itself to our mood at this time. Almost any noble verse may be read, either as his elegy or eulogy, or be made the text of an oration on him. Indeed, such are now discovered to be the parts of a universal liturgy, applicable to those rare cases of heroes and martyrs, for which the ritual of no church has provided.

The more conscientious preachers, the Bible men, they who talk about principle, and doing to others as you would that they should do unto you—how could they fail to recognize him, by far the greatest preacher of them all, with the Bible in his life and in his acts, the embodiment of principle, who actually carried out the golden rule?

When a noble deed is done, who is likely to appreciate it? They who are noble themselves. I was not surprised that certain of my neighbors spoke of John Brown as an ordinary felon, for who are they?

We soon saw, as he saw, that he was not to be pardoned or rescued by men. That would have been to disarm him, to restore him a material weapon, a Sharp’s rifle, when he had taken up the sword of the spirit—the sword with which he has really won his greatest and most memorable victories. Now he has not laid aside the sword of the spirit, for he is pure spirit himself, and his sword is pure spirit also.

I never hear of any particularly brave and earnest man, but my first thought is of John Brown, and what relation he may be to him. I meet him at every turn. He is more alive than he ever was. He has earned immortality.

(punctuation has been tweaked)

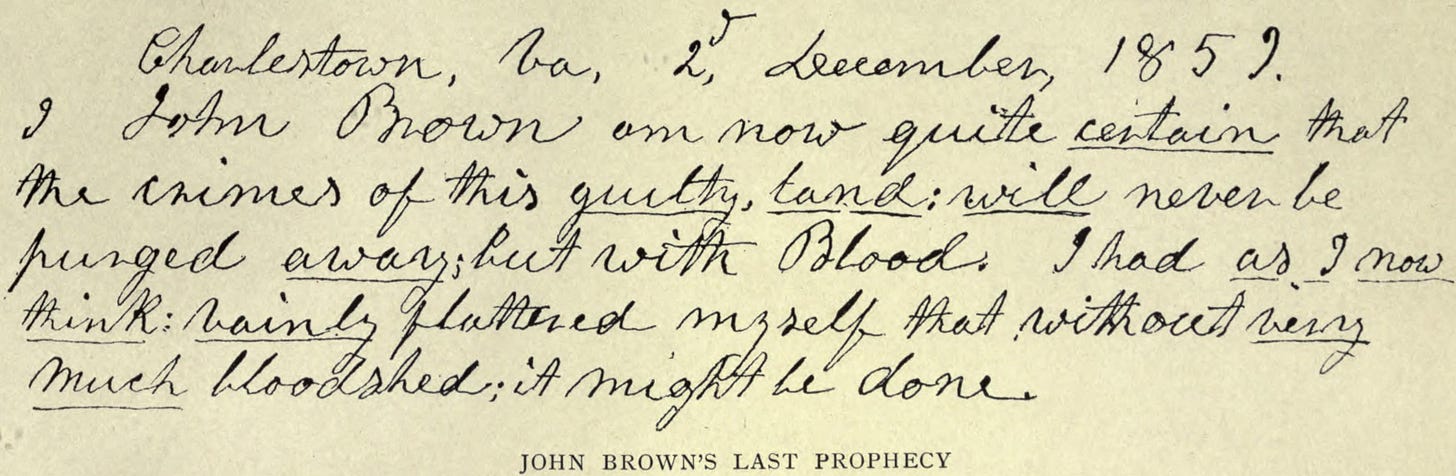

In his last letter to his family, two days before being executed, Brown wrote:

I am waiting the hour of my public murder with great composure of mind and cheerfulness, feeling the strong assurance that in no other possible way could I be used to so much advantage to the cause of good and of humanity, and that nothing that either I or all my family have sacrificed or suffered will be lost. […] I have now no doubt but that our seeming disaster will ultimately result in the most glorious success; so, my dear shattered and broken family, be of good cheer, and believe and trust in God with all your heart, and with all your soul; for He doeth all things well. Do not feel ashamed on my account, nor for one moment despair of the cause or grow weary of well doing. I bless God I never felt stronger confidence in the certain and near approach of a bright morning and a glorious day than I have felt, and do now feel, since my confinement here. I am endeavoring to return, like a poor prodigal as I am, to my Father, against whom I have always sinned, in the hope that he may kindly and forgivingly meet me, though a very great way off.

Thank you for your interest friends and enemies and internet strangers.